U.S. Immigration Policy and the Mental Health of Children and Families

- GAB NEWS

- Aug 25, 2025

- 9 min read

We are living in a time of heightened sociopolitical tension, when immigration policy in the United States has become not only a matter of legal regulation but a source of chronic fear, instability, and trauma for millions. The expansion of enforcement mechanisms—including worksite raids, prolonged and indefinite detention, and the erosion of protections in previously designated safe spaces—has transformed the landscape of daily life for immigrant families. For children and adolescents, these realities shape developmental trajectories, family systems, and mental health in profound ways. This includes not only children who are themselves immigrants but also the millions of U.S.-born children living in mixed-status households—children who, despite being citizens, are deeply affected by the precarious legal status and systemic exclusion faced by their caregivers.

Psychiatry, as both a clinical discipline and a social institution, cannot remain on the periphery. The current moment calls for a reexamination of how structural and intergenerational trauma are diagnosed, understood, and treated.

This article examines the mental health consequences of contemporary U.S. immigration enforcement on immigrant children and families, drawing from clinical vignettes, epidemiological data, and community-based research. We explore how trauma is transmitted across generations, how symptoms are shaped by sociopolitical forces, and how novel, culturally responsive models of care—including systems of care and community-partnered approaches—can provide more effective and ethical responses.

Scope of Problem

Children in immigrant families—whether they are immigrants themselves or born in the United States to immigrant parents—face a constellation of mental health risks shaped by the migration experience and the sociopolitical conditions of resettlement. Many of these risks are rooted in disruptions to caregiving relationships that occur both pre-migration and post-migration and are exacerbated by structural stressors such as economic hardship, discrimination, and immigration enforcement.

Pre-migration, it is common for parents to migrate ahead of their children, leaving them in the care of extended family, often for months or years. While intended to secure future safety and economic stability, these prolonged separations during sensitive developmental periods can undermine attachment security and increase children’s vulnerability to anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems (Suárez-Orozco, 2002). These risks are heightened when compounded by prior exposure to violence, poverty, and family loss in countries of origin—stressors shown to elevate the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health problems (Eisenman, et al., 2003; Blackmore, et al., 2020).

Post-migration, families often face chronic stress related to legal uncertainty, limited access to services, and fear of immigration enforcement. These stressors can affect both children and caregivers. Parents and caregivers living under the constant threat of detention or deportation frequently experience symptoms of depression, anxiety, and trauma, which can impair their emotional availability and disrupt the parent-child relationship (Concepción Zayas, et al., 2019). As noted by Fortuna, et al. (2019), Latina immigrant women are especially vulnerable due to intersecting stressors involving immigration status, trauma, and reproductive health, all of which can compromise maternal mental health and infant-caregiver bonding.

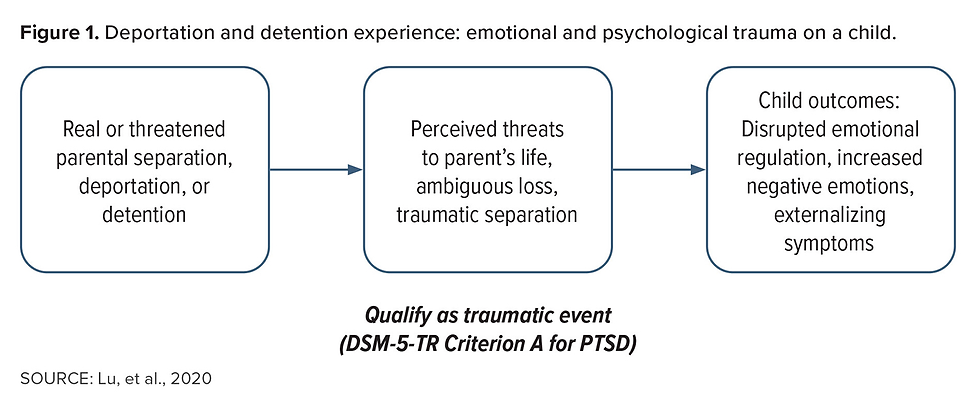

Forced family separations, particularly those resulting from immigration enforcement (e.g., detention, deportation), introduce acute psychological risks. A national study of 547 U.S.-born adolescents ages 11 to 16 found that having a detained or deported family member was associated with elevated risk for suicidal ideation, externalizing behaviors, and alcohol use (Roche, et al., 2020). In young children, abrupt caregiver loss has been linked to sleep and appetite disturbances, emotional dysregulation, and developmental regression (MacLean, et al., 2019). Forcible separation from a caregiver is recognized as an adverse childhood experience (ACE) that contributes to toxic stress, ambiguous loss, and long-term risk for psychiatric disorders (Roberts, et al., 2014; Lu, et al., 2020).

Even the threat of separation can generate profound emotional harm. Children in mixed-status families often live with chronic anticipatory anxiety that a loved one could be detained or deported. These fears have been shown to lead to school absenteeism, academic disengagement, and heightened emotional distress (Ramos-Sánchez & Llamas, 2024).

In sum, both voluntary pre-migration separations and involuntary post-migration disruptions—as well as the persistent threat of separation—have significant implications for child and family mental health. These experiences weaken attachment bonds, erode emotional security, and interfere with healthy development.

These dynamics underscore that immigration policy does not operate solely as a legal system—it functions as a structural determinant of health. Figure 1 illustrates the emotional and psychological impact of immigration enforcement—particularly detention and deportation—on children, highlighting how both real and threatened separations can undermine attachment, derail developmental processes, and contribute to persistent traumatic stress. This figure serves as a visual summary of how immigration enforcement becomes a formative, often traumatic, force in children’s lives.

Expansion of Immigration Enforcement

Over the past decade, U.S. immigration policy has become increasingly stringent and enforcement-driven (Human Rights Watch, 2024). Although the average daily number of individuals deported in 2025 has decreased by 10.9% compared with fiscal year 2024 (TRAC, 2025), the average daily number of individuals held in immigration detention has risen markedly (see Figure 2). This shift reflects a concerning trend: While deportations may be declining, more individuals are being subjected to prolonged and often indefinite detention. Further compounding the issue is the expanding legal ambiguity around who may be targeted for enforcement—including U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, non-immigrant visa holders, and undocumented individuals (Das, 2024). Enforcement actions are often applied inconsistently, and the lack of transparency has intensified fear and uncertainty within immigrant communities.

It is important to note that these data reflect trends only through midyear 2025, and the policy landscape remains highly volatile. With pending federal proposals and political shifts, future enforcement actions—including deportations, detentions, and workplace raids—may escalate further. Indeed, as this article was being finalized, President Donald Trump signed into law the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which included $150 billion for immigration enforcement and border security. For clinicians, educators, and policymakers, this uncertainty underscores the urgent need to understand how these evolving practices shape the daily realities and mental health of immigrant families.

Stable attachment to a caregiver is foundational to a child’s mental health. Today, the ripple effects of immigration enforcement extend into everyday environments once considered safe—such as schools, health care facilities, and community centers. As enforcement intensifies in these spaces, children in mixed-status families increasingly live with the fear that a routine day could result in detention or deportation of a loved one, which is associated with increased PTSD and internalizing symptoms (Rojas-Flores, et al., 2017). This chronic anxiety has led many children and adolescents to avoid school or withdraw from public life.

These behavioral changes are not merely reactions to isolated incidents but reflect the constant threat of family separation and systemic instability. Missed school days often translate into academic decline, social isolation, and missed opportunities for developmental support, including access to trusted adults and school-based mental health services. In this context, emotional distress becomes both an understandable and adaptive response to a life shaped by surveillance and exclusion. A clinical vignette—a composite case informed by real clinical encounters—illustrates how these ongoing structural stressors affect the mental health of youth living in mixed-status families (see “CASE STUDY: Ana, 17”). It highlights how immigration enforcement policies and pervasive legal uncertainty shape emotional functioning and daily life, underscoring the need for clinical approaches that recognize these broader social conditions.

Trauma-Informed, Relational, and Systemic Care Approaches for Immigrant Youth

Psychiatrists caring for immigrant children and adolescents affected by the trauma of detention, deportation, and structural exclusion must adapt their treatment models to expand beyond symptom reduction toward healing within context. The psychological toll of immigration enforcement is not only acute but chronic, layered, and developmental. It directly affects the brain and body, as well as the social networks and relational environments that children depend on for safety and identity formation.

Research in developmental neuroscience has shown that chronic, early-life stress—particularly when it involves attachment disruption, exposure to violence, or institutional betrayal—can dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and elevate cortisol levels over time. This, in turn, is associated with long-term impairments in emotional regulation, memory, impulse control, and cognitive development (Shonkoff, et al., 2012; Teicher & Samson, 2016), but trauma also disrupts developmental scaffolding—the relationships, routines, and educational supports that help children make meaning of their experiences and build resilience.

For immigrant children and citizen children in mixed-status families, these disruptions are often ongoing, with symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression emerging in the context of persistent structural instability. Standard treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha agonists may help reduce emotional reactivity and physiological distress. Likewise, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) provides a robust framework for processing trauma narratives and building coping skills. However, these interventions must be embedded within a broader ecosystem of care—one that attends the child’s relational, cultural, spiritual, and sociopolitical context (Fortuna, et al., 2023).

Components of a Holistic, Trauma-Informed Psychiatric Response

Relational and family-based care: The child does not heal in isolation. Engagement with caregivers is essential, particularly in immigrant families where trauma may be intergenerational. Psychiatrists can facilitate developmentally tailored sessions in which children and caregivers explore inherited narratives of migration, violence, and survival. Psychoeducation on trauma’s multigenerational effects can empower families to reframe symptoms as understandable responses to adversity, reducing stigma and shame.

Narrative and culturally grounded therapies: Immigrant children often carry unspoken or fragmented stories of loss, dislocation, and identity. Therapies that use storytelling, art, music, and movement—especially those grounded in the child’s cultural and spiritual heritage—offer powerful tools for restoring voice and meaning. Narrative exposure therapy, cuento (“stories”) therapy, and expressive arts practices can foster healing through connection to culture, ancestry, and collective awareness of sociogenic determinants of mental health (Costantino, et al., 2009; Neuner, et al., 2008).

Community and legal partnerships: Collaboration with community-based organizations (CBOs) can extend care beyond the clinic. CBOs provide families with access to immigration legal aid, parent-child support groups, and culturally meaningful healing practices (e.g., spiritual rituals, community circles). Psychiatric teams can develop trusted referral pathways and co-located services, reduce barriers, and integrate care into familiar, stigma-free settings.

School-based collaboration: Schools are critical sites for early identification and support—but they are also places where immigrant youth may experience trauma-related avoidance, disengagement, or behavioral challenges. Psychiatrists can advocate for trauma-informed school practices, help reduce reliance on punitive discipline, and ensure that students’ mental health needs are met with sensitivity to immigration-related stress.

Workforce development and policy advocacy: Addressing immigrant child trauma requires a linguistically and culturally responsive workforce, equipped with knowledge of structural trauma, migration histories, and family systems. Psychiatrists and mental health leaders can contribute to training programs, participate in community-based participatory research (CBPR)–informed initiatives, and advocate for policies that protect immigrant families from enforcement in sensitive locations such as schools and clinics.

Table 2 outlines how these types of interventions and approaches can be implemented across three interrelated levels—individual, interpersonal/community, and policy/societal—that together create a framework for addressing both clinical symptoms and the broader structural determinants of mental health. These interventions range from trauma-informed, language-concordant psychiatric care to community-rooted healing circles, promotora-led psychoeducation, mutual aid networks, and international rights–based policy frameworks. Multilevel, integrated strategies are therefore critical to restoring wellness, strengthening families, and advancing justice for immigrant children and adolescents.

Healing for immigrant children and families arises not only from clinical intervention but from the restoration and reinforcement of the protective relationships, cultural traditions, and communal ties that support resilience. Reconnection—with caregivers, extended family, cultural identity, and community networks—is foundational to recovery and long-term mental health. For immigrant youth, especially those navigating fear, displacement, or separation, healing also involves reclaiming safety, voice, and belonging in environments that may feel unpredictable or hostile.

Psychiatrists and mental health professionals occupy a critical position—not only as clinicians treating individual symptoms, but as informed witnesses to the broader harms of immigration policy and structural inequality. Their role must extend to advocating for reforms that reduce psychological harm, such as upholding protections for sensitive locations like schools and clinics, improving access to culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health care, and embedding trauma-informed practices across education, legal, and child welfare systems.

By naming and addressing trauma as a consequence of systemic and sociopolitical forces—not merely a private psychological experience—psychiatry can help reframe trauma as both a public health priority and a human rights issue. This shift allows for a deeper reckoning with the ways that chronic instability, racialized enforcement, and ambiguous loss affect child development and mental well-being. Mental health professionals can advance structural change by contributing clinical insights to interdisciplinary coalitions, supporting research on the emotional consequences of immigration enforcement, and engaging in community-based participatory approaches that reflect the lived realities of immigrant families. These collaborative efforts are essential to shaping policies and systems that affirm the dignity, developmental needs, and safety of children and families impacted by migration.

Ultimately, this work requires psychiatry to embrace a dual framework: one that is clinically precise and structurally aware—capable of addressing the psychological symptoms children present with, while also responding to the social, economic, and political forces that underlie those symptoms. Through systems-level collaboration, sustained advocacy, and culturally grounded care, psychiatry can contribute not only to the treatment of trauma but to the transformation of the conditions that produce it.

Conclusion

Immigrant children and families face layered forms of trauma that are not merely psychological but deeply embedded in structural and historical forces. The clinical consequences—ranging from PTSD and depression to somatic distress and suicidality—demand an approach that moves beyond symptom management to address the root causes of suffering. This includes recognizing the intergenerational impact of displacement, the toll of enforcement-driven immigration policy, and the daily stressors of life in a hostile sociopolitical environment. Effective care must be trauma-informed, culturally grounded, relationally centered, and community-partnered.

Psychiatrists and mental health professionals play a critical role—not only as clinicians but also as advocates, collaborators, and cultural interpreters—working across systems to promote healing, family integrity, and structural justice. The mental health of immigrant children is inseparable from the conditions in which they live, grow, and imagine their futures.

Comments